Executive Summary

The proposed China-Peru-Brazil railway, officially known as

the Bi-Oceanic Railway or Twin Ocean Railroad Connection, represents an

ambitious infrastructure initiative aimed at directly linking the Atlantic and

Pacific Oceans, thereby enhancing trade connectivity between South America and

Asia. Conceived decades ago and revived through recent high-level agreements,

particularly the July 2025 Memorandum of Understanding between Brazil and

China, the project seeks to significantly reduce shipping times and costs for

Brazilian commodities destined for Asian markets, bypassing the Panama Canal.

While the recently inaugurated Chinese-built Port of Chancay in Peru serves as

a critical Pacific gateway, the railway project remains in its feasibility

study phase, with a projected duration of up to five years for these

comprehensive technical, economic, logistical, and environmental assessments.

Despite its transformative economic potential for regional integration and

export efficiency, the project faces formidable challenges, including estimated

costs exceeding $70 billion, complex inter-country coordination, and significant

environmental and social concerns, particularly regarding its proposed routes

through the Amazon rainforest and proximity to indigenous territories. Past

failures of similar initiatives underscore the need for robust governance,

transparent impact assessments, and sustained political will to navigate these

hurdles and translate this grand vision into a tangible reality.

1. Introduction:

Bridging Continents and Markets

1.1 Project Concept

and Strategic Vision

The Transcontinental Railway Brazil-Peru, also known as the

Twin Ocean Railroad Connection (Chinese: 两洋铁路)

or the Brazil-Peru Bi-oceanic Corridor, is a monumental rail project designed

to forge a direct link between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.1

This initiative is fundamentally aimed at increasing commerce between Brazil

and Peru and, more broadly, at enhancing South America's integration with and

access to Asian markets, especially China.1 The project's

overarching goal is to facilitate a more direct and efficient trade route for

Brazilian goods, particularly agricultural and mineral commodities, to reach

Asia, thereby reducing reliance on the Panama Canal.3 This direct

connection is projected to shorten shipping times to Asian markets by as much

as 10 to 12 days, offering substantial logistical advantages and cost

reductions for Brazilian exports.3

The strategic vision extends beyond mere transportation; it

seeks to unlock the full potential of connecting the Brazilian and Peruvian

railway networks, positioning Brazil as a pivotal "bridge between the

Atlantic and the Pacific".2 This project is seen as a key

component of Brazil's broader "South American Integration Routes"

initiative, launched in 2023, which prioritizes connecting road, river, and

rail networks in border areas with neighboring countries.7 For

China, the railway aligns with its broader Belt and Road Initiative (BRI),

fostering economic interdependence and regional development in the Global South

by addressing infrastructure gaps and promoting its economic and political

interests.3 The project signifies a strategic step for Brazil's

transportation sector, aiming to attract investment and promote deeper regional

and international integration with countries in Latin America and Asia.5

1.2 Historical

Context and Evolution

The concept of a transcontinental railway linking Brazil and

Peru is not new, with discussions dating back to the 1960s.2

However, substantial progress on this ambitious vision began more recently. On

March 19, 2008, the Peruvian Congress declared the project to be of national

interest, signaling early commitment.1 In 2011, former Colombian

President Juan Manuel Santos even disclosed discussions with China for an

inter-ocean railway, though this "Dry Canal" project was distinct from

the Brazil-Peru initiative.1

A significant milestone occurred on July 16, 2014, when

China, Brazil, and Peru collectively released a joint statement indicating

their commitment to cooperate on a bi-ocean railway.1 This

"Joint Statement by China, Brazil, and Peru regarding the Bi-Oceanic

Railway Project cooperation" delineated a plan for a railway extending

westward from the southeastern Brazilian state of Rio de Janeiro to the port of

Callao in Peru.1 Following this, from May 6 to 14, 2015, a task group

from China's National Development and Reform Commission visited Brazil and Peru

to discuss the project's promotion.1 On May 19, 2015, China and

Brazil executed a collaborative five-year agreement, and a Memorandum of

Understanding (MOU) was signed by China, Brazil, and Peru for the joint

conduction of basic feasibility studies.1 Under this agreement,

China Railway Eryuan Engineering Group (CREEC) was tasked with undertaking a

basic feasibility study in collaboration with the host countries' ministries of

transportation.9

Despite these initial agreements, the construction of the

Bi-Oceanic Railway failed to achieve significant advancement in the years that

followed.1 This stagnation was primarily due to political

instability in Brazil and economic challenges in other Latin American nations.1

Furthermore, a critical factor in the project's slowdown was a clash between

Chinese and Brazilian interests, particularly regarding the use of technical

standards, with Brazil rejecting a Chinese-provided feasibility study due to

its perceived poor quality and lack of in-depth social-environmental impact

analysis.8 The study even controversially proposed changing local

laws to reduce the perimeter of a national park for project implementation.8

Brazil confirmed in 2018 that it had dropped the railway to the Pacific for

China exports, citing costs and Peru's environmental concerns.8

The project concept experienced a pivotal resurrection with

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva's resurgence to power in Brazil in 2023.1

Brazil's current transportation infrastructure predominantly depends on road

travel, rendering trains essential for the nation's future advancement and

providing renewed impetus for the railway.1 The inauguration of the

Chinese-built Chancay Port in Peru in November 2024 further reignited Brazil's

interest in enhancing connectivity with China, as this port is envisioned as a

major Pacific gateway for the railway.2 This renewed interest

culminated in a significant agreement on July 7, 2025, when Brazil and China

signed a memorandum of understanding to initiate joint studies for the

construction of a rail corridor connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans,

marking the latest development in the project's long history.4

2. Project Details

and Proposed Routes

2.1 Current Main

Route and Brazilian Section

The main proposed route for the bi-oceanic railway spans

approximately 6,500 kilometers.2 It is designed to commence at the

Port of Chancay on Peru's Pacific coast, traverse the Andes Mountains at an

altitude of 4,818 meters heading northeast, cross the Amazon rainforest along

the Peru-Brazil border, connect with Brazil's under-construction east-west

integrated railway FICO-FIOL in Porto Velho, and ultimately reach the Atlantic

port of Ilhéus in the state of Bahia.2

On the Brazilian side, the project's primary focus involves

actively promoting the construction of the FICO-FIOL (West-East Integration

Railway and Center-West Integration Railway) lines.2 These railways

are central to the new route and are intended to run from east to west,

starting at the Atlantic port of Ilhéus.2 The Brazilian government's

plan, as disclosed in the July 2025 MoU, indicates the Bioceanic Railway will

begin in the city of Lucas do Rio Verde, in the state of Mato Grosso.5

From there, it is planned to pass through the border with Bolivia, cross the

entire state of Rondônia, and continue through southern Acre, near the Peruvian

border.5 This route aims to integrate Brazil's existing and planned

railway networks, specifically the West-East Integration (FIOL), Center-West

Integration (FICO), and North-South Railway (FNS).7

The FIOL and FICO segments that form part of the bi-Oceanic

corridor are divided into three sections, reflecting varying stages of

development 2:

● FIOL 1: Stretching 537 kilometers from

Ilhéus to Caetité in the state of Bahia, this section has already been

completed.2

● FIOL 2: Running 485 kilometers from

Caetité to Barreiras, also in Bahia, this segment is currently under

construction.2

● FIOL 3: Covering 838 kilometers from Barreiras

to Mara Rosa in the state of Goiás, this section is still in the project

research phase.2

A significant challenge on the Brazilian side is the

conceptual nature of the segment from Lucas do Rio Verde to Acre on the

Peruvian border, where no actual project is currently in place.2

This unbuilt stretch represents nearly half of the Brazilian portion of the

corridor, highlighting the substantial work still required.2 The

total length of the corridor within Brazil is estimated to involve more than

4,000 kilometers of track, with less than 15% currently ready.2

2.2 Peruvian Section

and Connection to China

The Peruvian section of the railway is critical for

connecting South America to Asian markets. The planned line will extend from

the Peruvian border to the Port of Chancay, which was built by China and

inaugurated in November 2024.2 This deepwater port, located just 70

kilometers from Lima, is a cornerstone of the project, envisioned as a major

transshipment hub for goods moving between Asia and South America, potentially

reducing reliance on the Panama Canal.2 COSCO Shipping, a Chinese

state-owned company, holds a 60% stake and exclusive operating concession for

the Chancay Port.2

Railway construction in Peru is still in the preliminary

research stage.2 In March 2025, Peru's Ministry of Transport and

Communications (MTC) announced the launch of pre-investment studies for the

Trans-Andean railway project.2 These studies are comprehensive,

including route surveys, station planning, mapping, and cost estimation.2

This Trans-Andean railway is projected to cross the Andes Mountains and reach

the Amazon rainforest region, with a total length of approximately 900

kilometers.2 Upon completion, it is expected to be the longest

railway trunk line in Peru.2 The Peruvian section alone is estimated

to require over USD 14 billion in investment and is planned to be developed

under a public-private partnership (PPP) model.2

The connection to China is facilitated through the maritime

route from the Port of Chancay across the Pacific Ocean.5 The

railway's primary purpose is to streamline the transport of Brazilian goods to

this Pacific port, from where they can be shipped directly to Shanghai Port in

China, significantly shortening export times.5 This logistical

overhaul is a key driver for China's involvement, as it seeks to enhance trade

efficiency with its major commodity suppliers in South America.3

2.3 Bolivian

Alternative Route

While the direct Brazil-Peru route is the primary focus of

recent agreements, a Bolivian alternative route has also been under

consideration for the transcontinental railway project.15 This

proposed route, also known as the Central Bi-Oceanic railway, aims to connect

the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans via Bolivia.15 The project was

initially brought up in 2013 by heads of state Evo Morales of Bolivia and Xi

Jinping of China as an alternative to maritime shipping between China and South

America's Atlantic coast.15

On December 6, 2017, the heads of state of Brazil and

Bolivia signed an agreement regarding this alternative track.15

Currently, there are two potential routes under discussion for the Bolivian

corridor: one from Santos, Brazil, to Ilo, Peru, and another from Santos,

Brazil, to Matarani, Peru.15 This route was estimated to cost €12

billion in 2017 and $72 billion circa 2023.15

The Bolivian route offers a different set of logistical and

geopolitical considerations. While the Brazil-Peru direct route is more focused

on Chinese trade interests and leverages the Chancay megaport, the Bolivian

corridor reflects a broader regional push for economic integration, even

including Paraguay.13 However, recent developments suggest that the

direct Brazil-Peru route, particularly with the operationalization of the

Chancay Port, appears to be the more feasible and prioritized option.13

Despite this, the Bolivian route is still officially under consideration,

indicating the complexity of regional infrastructure planning and the desire

for multiple options for transcontinental connectivity.15

3. Objectives and

Motivations

3.1 Economic Drivers

The primary economic driver for the Brazil-Peru-China

railway is the significant reduction in trade logistics costs and transit

times.3 By providing a direct rail link from Brazil’s Atlantic coast

to Peru’s Pacific coast, the project aims to shorten export times to Asia by up

to 10 to 12 days compared to current routes that necessitate passage through

the Panama Canal.3 This reduction in transit time and distance,

estimated to be as much as 10,000 kilometers, directly translates into lower

shipping costs for Brazilian commodities, making them more competitive in Asian

markets.3

Brazil, as a major global exporter of raw materials,

particularly soybeans, corn, iron ore, copper, and beef, stands to gain immensely

from this enhanced connectivity.1 The proposed route will commence

from Brazil's industrial zone in the southeast, pass through the "Iron

Quadrangle" iron ore region, the agricultural belt of Goiás State, and the

copper mining area of the Andes Mountains – all vital resource zones.1

This direct access to the Pacific is expected to boost the export volumes and

revenues for these key sectors, stimulating the domestic economy by increasing

production demands and creating jobs.3 Improved transport connectivity

also creates development opportunities in less industrialized regions, such as

Acre and Tocantins, by enhancing their infrastructure and integrating them into

global supply chains.3

For China, the railway serves as a crucial means to secure

and diversify its supply chains for essential commodities from South America.3

China's capability in infrastructure, equipment manufacturing, and

railway-building expertise positions it as an ideal partner, and its

investments, often channeled through mechanisms like the China–Brazil Fund for

the Expansion of Production Capacity, are aimed at promoting trade and

development across the Global South.3 The project is also seen as a

key factor in unlocking the full potential of the recently inaugurated Chancay

megaport in Peru, which, without a direct rail connection to Brazil, would have

limited utility as a regional hub.5

3.2 Geopolitical and

Strategic Imperatives

Beyond economic benefits, the Brazil-Peru-China railway

carries significant geopolitical and strategic implications for all involved

nations and the broader region. For Brazil, the project represents a strategic

step towards strengthening its ties with Asia and diversifying its trade

routes, reducing its logistical dependence on traditional maritime corridors.5

By positioning itself as a "bridge between the Atlantic and the

Pacific," Brazil enhances its regional influence and integration within

South America.4 This aligns with Brazil's broader "South

American Integration Routes" initiative, which prioritizes cross-border

infrastructure to connect complementary economies.4

For China, the railway is a tangible manifestation of its

growing influence in Latin America, particularly through infrastructure

investments.10 China has significantly expanded its economic and

geopolitical footprint in the region, with trade exceeding $518 billion in 2024

and projected to reach over $700 billion by 2035.18 Investments in

critical infrastructure like ports and railways, including the Bioceanic

Railway Corridor, are key to this expansion.10 This project, if

completed, could reshape trade flows in South America and offer an alternative

to the Panama Canal, potentially giving China significant geopolitical leverage

by controlling key infrastructure assets.5 This capability could, in

a global conflict or trade dispute, be used to disrupt shipping routes or exert

pressure on other nations, which raises concerns for countries like the United

States.10

The project also reflects China's broader foreign policy

objectives, such as the "Harmonious World" and "Peaceful

Development" ideologies, intertwined with strategic imperatives to foster

economic interdependence.8 While some critics voice concerns about

potential "debt traps" and lower environmental and labor standards

associated with Chinese loans and projects, China views these initiatives as a

means to promote economic development and cooperation with the Global South.9

The railway's advancement, particularly with the operational Chancay Port,

establishes a new land-and-sea connectivity link between Asia and Latin

America, reinforcing China's strategic presence.13

The United States has historically viewed Latin America as

its sphere of influence, and China's increasing encroachment and control over

critical infrastructure assets in the region have prompted calls for increased

U.S. engagement and investment to counter China's growing sway.10

The competition for influence in Latin America underscores the project's

broader geopolitical significance, as it could shift the balance of power in

the region.10

4. Key Stakeholders

and Their Roles

The Brazil-Peru-China railway project involves a complex web

of stakeholders, each with distinct roles, interests, and levels of influence.

Understanding these actors is crucial for comprehending the project's dynamics

and challenges.

4.1 Governments and

State Entities

The governments of Brazil, Peru, and China are the primary

drivers and decision-makers for this transcontinental railway.1

● Brazil: The Brazilian government,

particularly through its Ministry of Transport and the state-owned company

Infra S.A., is a key proponent. Brazil's National Secretary of Railway

Transportation, Leonardo Ribeiro, has emphasized the project as a

"strategic step for the transportation sector in Brazil" and an

"essential partnership".5 The project is integrated into

Brazil's "South American Integration Routes" initiative, led by the

Ministry of Planning and Budget, which aims to connect regional transport

networks.7 President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva's government views

access to the Pacific as essential for strengthening ties with Asia and

boosting exports.12

● Peru: The Peruvian government, through

its Ministry of Economy and Finance and Ministry of Transport and Communications

(MTC), has expressed an optimistic disposition towards the project.1

Peru's Economy Minister Raul Perez Reyes has actively sought high-level

meetings with Chinese and Brazilian counterparts to advance the railway.14

The Peruvian Congress declared the project of national interest as early as

2008.1

● China: China is a crucial partner,

providing significant investment, technical expertise, and railway-building

capabilities.3 The China Railway Economic and Planning Research

Institute, part of China State Railway Group, is responsible for coordinating

feasibility studies with Brazilian counterparts.5 China's ambassador

to Peru, Song Yang, has been directly involved in high-level discussions.14

The project aligns with China's broader Belt and Road Initiative, aiming to

foster economic interdependence and promote its global economic and political

interests.8

4.2 Corporations and

Financial Institutions

Several corporate and financial entities play pivotal roles

in the project's development and funding.

● China Railway Eryuan Engineering Group

(CREEC): This Chinese state-owned company was initially put in charge of

undertaking basic feasibility studies in collaboration with host countries'

ministries of transportation in 2015.9

● Infra S.A. (Brazil): A Brazilian

state-owned company under the Ministry of Transport, Infra S.A. is responsible

for conducting joint studies with China's railway research institute.6

● COSCO Shipping (China): This Chinese

shipping giant is a significant entity due to its exclusive rights to operate

the new Chancay "mega port" in Peru, a critical Pacific terminus for

the railway.2 COSCO Shipping's investment and operational control

over Chancay underscore the port's strategic importance to the overall railway

vision.2

● China Development Bank & New

Development Bank: These Chinese-led financial institutions are crucial for

funding large-scale infrastructure projects in the Global South, including

potential railway developments.1 China's investment in Brazil, for

example, is partly made via the China–Brazil Fund for the Expansion of

Production Capacity.3

4.3 Civil Society and

International Observers

The project has also drawn significant attention and

scrutiny from various civil society organizations, indigenous groups, and international

observers.

● Environmental Activists and NGOs:

Groups such as Greenpeace, SOS Amazonia, Friends of the Earth Peru, Derecho

Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (DAR), Conservación Internacional, and Survival

International have voiced strong concerns about the project's potential

environmental impact, particularly on the Amazon rainforest and protected

areas.11 They warn of deforestation, land use change, and increased

mining, advocating for robust environmental impact assessments and

transparency.11

● Indigenous Organizations and Local

Communities: Organizations like OPIN (Acrean indigenous organization) and

anthropological associations have warned about the railway's indirect effects

on indigenous communities and the potential for forced displacement, loss of

livelihood, and cultural disruption, especially if routes cross indigenous

reserves.11 Their concerns highlight the social dimensions of

large-scale infrastructure development.11

● Analysts and Researchers: Institutions

like ANBOUND, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and the Centre for

China and Asia-Pacific Studies in Lima provide critical analysis on the

project's geopolitical, economic, and socio-environmental implications.2

Their assessments often highlight the complexities, risks, and potential

shortcomings of such mega-projects.2

● United States: The U.S. government and

various think tanks observe China's growing influence in Latin America with

unease, urging vigilance on Chinese investments due to concerns about debt

traps, lower standards, and national security risks related to control over

critical infrastructure.10 This international scrutiny adds another

layer of complexity to the project's geopolitical landscape.

5. Shipping Time and

Cost

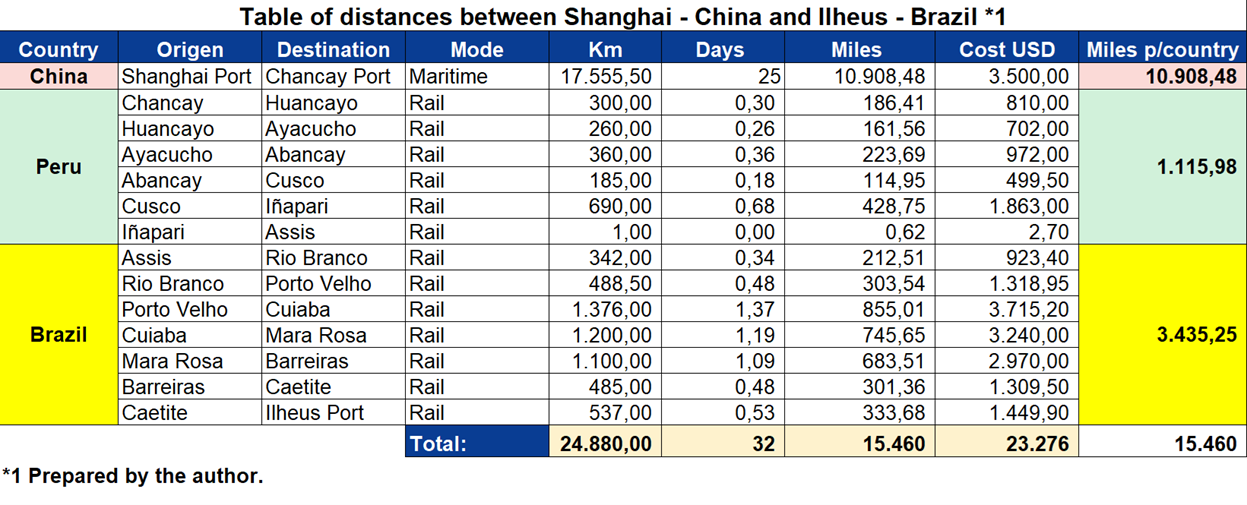

We analyzed the case of a client in Ilhéus, Brazil, who

decided to purchase two electric vehicles manufactured in China.

5.1 Product to be

Imported

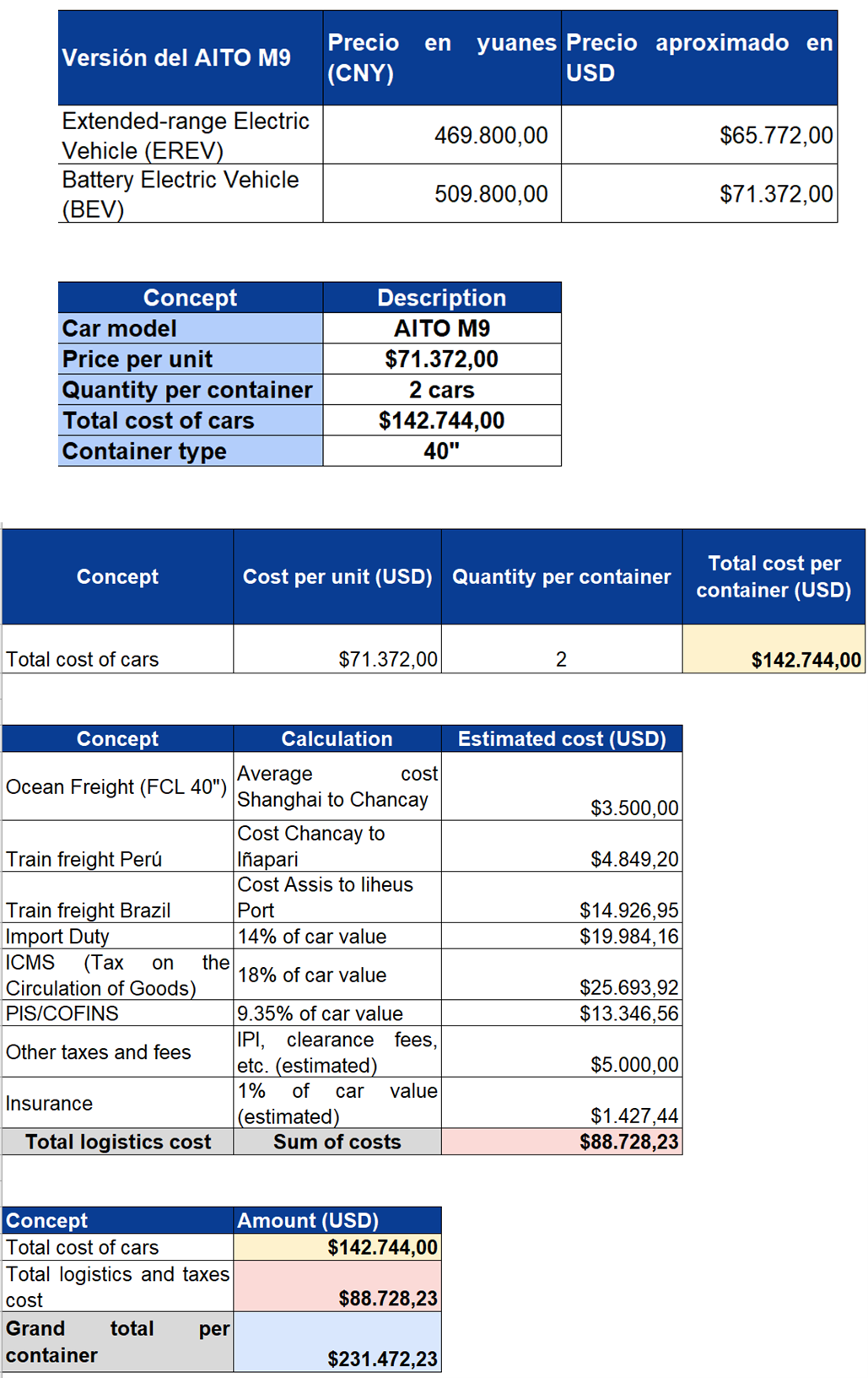

Product: AITO M9

Quantity: 2

Container: 1 x 40"

Origin: Shanghai - China Destination: Ilheus –

Brazil

Total Miles per

Country

5.3. Cost Analysis of

the Route via Chancay (Peru)

The total estimated cost to transport one container with

cars from Shanghai to Ilheus, following the route that passes through the port

of Chancay and continues by train, is $231,472.23.

Below is a table with the estimated costs for the brazilian

importer, broken down into the main components of the route:

Based on this estimate, moving one container would take

approximately 32 days to travel from Shanghai to Ilhéus Port.

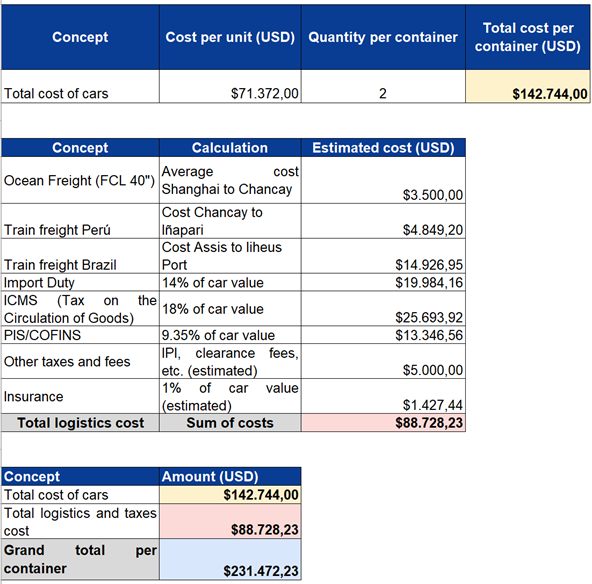

5.4. Cost Analysis of

the Route via the Panama Canal

The total estimated cost to transport one container with

cars from Shanghai to Ilheus, following the route that passes through the

current Panama Canal, is $215,196.08.

Below is a table with the estimated costs for the Brazilian

importer, broken down into the main components of the route:

Based on this estimate, moving one container would take

approximately 30 to 45 days to travel from Shanghai to Ilhéus Port.

Formula Explanations

6. Current Status and

Latest Developments (As of July-August 2025)

The Brazil-Peru-China railway project, after periods of

stagnation, has seen a significant revival of interest and concrete steps

towards its realization in 2025.

6.1 Feasibility

Studies and Agreements

The most recent and pivotal development occurred on July 7,

2025, when Brazil and China signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to

launch joint studies for the construction of the rail corridor.4

This agreement marks a crucial step, committing both nations to a comprehensive

assessment of the project's viability.6

The feasibility study, which is projected to take up to five

years, will cover technical, economic, logistical, and environmental factors to

ensure the long-term sustainability of the transcontinental route.5

The Brazilian Ministry of Transport (through Infra S.A.) and the China Railway

Economic and Planning Research Institute of China State Railway Group are

responsible for coordinating these studies.5 This signifies a

renewed, structured approach to addressing the complex challenges that

previously hindered the project's progress.

Prior to this MoU, there were clear signals of renewed

engagement. In April 2025, a delegation of Chinese government railway engineers

visited Brazil's FICO and FIOL railway lines, which are anticipated to be

important components of the larger corridor.2 This on-site

assessment demonstrated China's practical interest and commitment to

understanding the existing infrastructure and potential integration points.6

6.2 Progress on Brazilian

and Peruvian Infrastructure

While the transcontinental link is still in the study phase,

progress continues on key segments within Brazil and Peru that are intended to

form part of the larger bi-oceanic corridor.

Brazilian Side:

● FIOL-FICO Railways: Brazil's primary

focus has been on promoting the construction of the FICO-FIOL railway, which

runs from the Atlantic port of Ilhéus to the inland port of Porto Velho.2

○

FIOL 1

(Ilhéus to Caetité): This 537-kilometer section has been completed.2

○

FIOL 2

(Caetité to Barreiras): This 485-kilometer section is currently under

construction.2

○

FIOL 3

(Barreiras to Mara Rosa): This 838-kilometer section is still in the

project research phase.2

● Conceptual Gap: A significant portion

of the Brazilian route, specifically the stretch from Lucas do Rio Verde to

Acre on the Peruvian border, remains a conceptual plan with no actual project

in place.2 This segment represents nearly half of the Brazilian

portion of the corridor, indicating the scale of future construction required.2

● Investment Plans: The Brazilian

government has demonstrated its commitment through financial allocations,

including USD 776 million from the national budget for 2025 to support the

South American integration route plan.2 In February 2025, Brazil

unveiled a USD 17 billion railway investment plan aimed at increasing rail

transport's share in exports.2

Peruvian Side:

● Port of Chancay: The construction of

the Port of Chancay, a crucial Pacific terminus for the railway, has been

completed.2 Phase I of the port officially began operations in

November 2024.2 This Chinese-built megaport is a significant enabler

for the railway project, as it provides the necessary deepwater access for

large vessels connecting to Asia.2

● Trans-Andean Railway Studies: In March

2025, Peru's Ministry of Transport and Communications (MTC) announced the

launch of pre-investment studies for the Trans-Andean railway project.2

This approximately 900-kilometer railway will cross the Andes Mountains and reach

the Amazon rainforest region, forming a vital link in the overall

transcontinental route.2 These studies are essential groundwork

before any construction can commence.2

● High-Level Discussions: On May 26,

2025, the Peruvian Ministry of Economy and Finance and the Ministry of

Transport and Communications released a statement indicating their readiness to

pursue high-level discussions with Chinese officials and business

representatives to advance the bi-oceanic railway.1 This indicates

Peru's proactive stance in moving the project forward.

Overall, while significant progress has been made in

planning and preliminary studies, particularly with the recent Brazil-China MoU

for feasibility studies, the actual construction of the full transcontinental railway

remains a massive undertaking, with only a fraction of the necessary track in

Brazil currently ready.2 The project is still in a preparatory

phase, with the next five years dedicated to comprehensive assessments before

any final commitments on route selection or construction can be made.6

7. Challenges and

Controversies

The ambitious scope of the Brazil-Peru-China railway project

is matched by a formidable array of challenges and controversies, spanning

financial, political, logistical, environmental, and social dimensions. These

complexities have historically impeded progress and continue to necessitate

careful navigation.

7.1 Financial and

Logistical Hurdles

The sheer scale of the project presents immense financial

and logistical hurdles. Estimates for the total cost of the transcontinental

corridor range from $70 billion to $72 billion, making it one of the most

expensive infrastructure projects ever proposed in South America.6

Within Brazil alone, the project involves more than 4,000 kilometers of track,

of which less than 15% is currently ready.2 This indicates a massive

undertaking requiring substantial capital investment and long-term financial

commitment.

A key financial concern is the ability to recoup such

significant costs, especially given past projects of this nature have struggled

with economic viability.16 The design primarily relies on

integrating existing and under-construction Brazilian railway routes

(FIOL-FICO), but the crucial segment from Lucas do Rio Verde to the Peruvian

border is still only a conceptual plan, lacking concrete project development.2

This gap represents nearly half of the Brazilian portion of the corridor,

underscoring the substantial investment still required for new construction.2

Logistically, crossing the diverse and challenging South

American terrain poses immense technical difficulties. The route must traverse

the Andes Mountains, requiring extensive tunnels and bridges, which

significantly push costs higher.2 Furthermore, navigating the vast Amazon

rainforest presents unique engineering and logistical challenges, demanding

innovative solutions to minimize environmental disruption while ensuring

operational efficiency.2 The coordination of such a massive project

across two countries with different existing railway standards and operational

practices also adds layers of logistical complexity.3

7.2 Political and

Coordination Obstacles

Political instability and a lack of consistent inter-country

coordination have been significant impediments to the project's advancement.

Past failures, such as the stagnation after the 2014-2015 agreements, were

partly attributed to political instability in Brazil and economic stagnation in

other Latin American nations.1

A fundamental challenge identified in previous attempts was

a clash between Chinese and Brazilian interests.8 Specifically,

Brazil required the use of local technical standards, while China sought to

promote its own.9 This divergence, coupled with a Chinese-provided

feasibility study that Brazil deemed of poor quality and lacking in-depth

social-environmental analysis, led to Brazil's rejection of the study and a

subsequent abandonment of the initiative in 2018.8 This highlights

the critical importance of aligning technical standards and ensuring mutual

agreement on project methodologies and impact assessments.

More recently, the signing of the July 2025 MoU between

Brazil and China triggered unease in Peru, as Peruvian officials were not

formally involved in the signing, despite the project passing through their

territory.12 Some local media described this as a violation of

Peru's sovereignty, underscoring the delicate diplomatic balance required for

such a trilateral undertaking.12 This incident demonstrates that

despite renewed political will, ensuring transparent and inclusive coordination

among all three sovereign nations remains a sensitive and ongoing challenge.3

Without solid economic grounds and guaranteed funding, and given these

political tensions, there is a real risk the railway could remain little more

than a grand vision.12

Moreover, the project is situated within a broader

geopolitical context of rising unease in Washington over China's growing

economic influence in the Western Hemisphere.10 This external

scrutiny adds a layer of political complexity, as the U.S. urges vigilance on

Chinese investments and seeks to increase its own engagement in Latin America

to counter China's sway.10

7.3 Environmental and

Social Concerns

The proposed railway traverses ecologically sensitive regions,

including significant portions of the Amazon rainforest, the Andes Mountains,

and areas within Brazil's "Arc of Deforestation," raising profound

environmental and social concerns.6 Environmental activists and

civil society organizations have voiced strong opposition, warning that the

project could accelerate deforestation and degradation in these vital biomes.11

Key environmental concerns include:

● Deforestation and Biodiversity Loss:

The railway's construction, particularly the segments built from scratch into

the Amazon, could lead to significant deforestation and loss of vegetation

cover, impacting biodiversity and sensitive ecosystems.11 The Amazon

is characterized by a lack of state presence and oversight, which intensifies

fears that new infrastructure could exacerbate illegal logging, land-grabbing,

and agricultural expansion.17

● Impact on Protected Areas and Indigenous

Lands: While Brazilian planners have altered some routes to avoid directly

cutting through Indigenous lands or protected forest areas, concerns remain.17

The railway will pass close to several protected territories, potentially

driving the conversion of remaining forest areas crucial to indigenous peoples.17

Previous routes were criticized for crossing indigenous reserves and national

parks, highlighting the need for careful route selection and impact mitigation.8

The FICO railway, part of the corridor, already threatens the headwaters of the

Xingu River, impacting the Xingu Indigenous Park.17 Altering

conservation laws to make way for tracks would be far from straightforward.12

● Historical Patterns of Destruction:

Critics point to the negative impacts of past infrastructure projects, such as

the Trans-Amazonian Highway, which led to massive deforestation and endangered

native peoples through increased violence from illegal loggers and cattle

ranchers.11 There is concern that the railway could repeat these

patterns, especially given the weak state oversight and ongoing dismantling of

environmental licensing frameworks in Brazil.17

Social concerns revolve around the potential for forced

displacement, loss of livelihood, and disruption of traditional knowledge and

practices for indigenous groups and other traditional communities living along

the proposed routes.11 The lack of transparency about the full

assessment of commercial, social, and environmental impacts has been a

persistent criticism.11

While proponents argue that railways are generally more

environmentally friendly than highways and that the project aims for sustainable

development by reducing greenhouse gas emissions compared to road transport,

the scale and location of this project demand rigorous environmental and social

safeguards.3 The feasibility study is expected to account for these

significant environmental hurdles, but both parties remain in the study phase

and have not made final commitments on environmental mitigation.6

8. Conclusions

The Brazil-Peru-China transcontinental railway project

represents a strategic and ambitious endeavor with the potential to

significantly reshape trade flows between South America and Asia, offering a

direct trans-oceanic link that bypasses the Panama Canal. The renewed

commitment, particularly evidenced by the July 2025 Memorandum of Understanding

between Brazil and China and the operationalization of Peru's Chancay Port,

signals a determined effort to advance this long-envisioned infrastructure. The

economic drivers are clear: reduced shipping times and costs for Brazilian

commodities, enhanced market access for both South American and Asian

economies, and the stimulation of regional development.

However, the project's path forward is fraught with

substantial challenges. The estimated cost, exceeding $70 billion, demands

immense financial commitment and raises questions about long-term viability and

funding mechanisms. Logistical complexities, particularly traversing the Andes

and the Amazon, necessitate advanced engineering and careful planning.

Crucially, political and coordination obstacles, including historical clashes

over technical standards and recent concerns about Peru's formal involvement in

key agreements, underscore the need for robust, transparent, and inclusive

trilateral governance.

Perhaps the most critical considerations revolve around the

profound environmental and social impacts. The proposed routes through the

Amazon rainforest and proximity to indigenous territories raise serious

warnings about deforestation, biodiversity loss, and the displacement of local

communities. The historical patterns of destruction associated with large-scale

infrastructure in the Amazon, coupled with concerns over weak environmental

oversight, demand that environmental and social safeguards are not merely

considered but are rigorously implemented and consistently monitored.

In conclusion, while the vision of a transcontinental

railway connecting Brazil, Peru, and China holds immense promise for economic

integration and trade efficiency, its realization hinges on the ability of the

involved nations to effectively address the formidable financial, political,

and environmental hurdles. The current feasibility study phase is critical,

requiring comprehensive and transparent assessments that genuinely incorporate

social and environmental considerations alongside technical and economic

viability. The success of this mega-project will ultimately depend on sustained

political will, robust trilateral coordination, and an unwavering commitment to

sustainable development practices that balance economic aspirations with

ecological and social responsibilities. Without these foundational elements,

the grand vision risks remaining an unfulfilled ambition.

Works cited

1. Transcontinental railway Brasil-Peru - Wikipedia, accessed August 5, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transcontinental_railway_Brasil-Peru

2. Challenges In The Development Of The South American Bi-Oceanic ..., accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.eurasiareview.com/10062025-challenges-in-the-development-of-the-south-american-bi-oceanic-railway-analysis/

3. The

New Route to Development: Chinese Investments in Brasil's Railways - Brics,

accessed August 5, 2025, https://brics.br/en/news/articles/the-new-route-to-development-chinese-investments-in-brasils-railways

4. Brazil

and China promote strategic project to connect the Atlantic and Pacific -

Aduana News, accessed August 5, 2025, https://aduananews.com/en/brasil-y-china-impulsan-proyecto-estrategico-para-conectar-atlantico-y-pacifico/

5. China,

Brazil sign MoU to conduct feasibility study for ... - Global Times, accessed August

5, 2025, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202507/1337961.shtml

6. South

America Explores Building Own 2,800-Mile Transcontinental Railroad - Newsweek,

accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.newsweek.com/south-america-transcontinental-rail-2097141

7. Brazil,

China sign agreement to plan railroad to Peru | Agência Brasil, accessed August

5, 2025, https://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/en/economia/noticia/2025-07/brazil-china-sign-agreement-plan-railroad-peru

8. China-backed

infrastructure in the Global South: lessons from the ..., accessed August 5,

2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/366621204_China-backed_infrastructure_in_the_Global_South_lessons_from_the_case_of_the_Brazil-Peru_Transcontinental_Railway_project

9. China-backed

Infrastructure in the Global South: Lessons from the Case of the Brazil-Peru

Transcontinental Railway Project, accessed August 5, 2025, https://cechap.up.edu.pe/wp-content/uploads/Working-Paper-Nro2-Leolino-Dourado.pdf

10. China's Growing Influence in Latin

America - Braumiller Law Group, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.braumillerlaw.com/chinas-growing-influence-in-latin-america-infrastructure-investments-and-implications-for-the-panama-canal/

11. Controversial Amazon route of

Transcontinental Railway Brazil-Peru - Global Atlas of Environmental Justice,

accessed August 5, 2025, https://ejatlas.org/print/opposition-against-controversial-amazon-route-of-transatlantic-railway-brazil-peru

12. Brazil and China to study South

American transcontinental railway project - The Star, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.thestar.com.my/aseanplus/aseanplus-news/2025/07/12/brazil-and-china-to-study-south-american-transcontinental-railway-project

13. New Corridor, New Strategy: China's

Bi-Oceanic Railway and Latin America's Trade Route Battleground, accessed

August 5, 2025, https://chinaglobalsouth.com/analysis/china-central-bi-oceanic-railway-latin-america/

14. Peru Seeks Rail Meeting with China,

Brazil - The China-Global ..., accessed August 5, 2025, https://chinaglobalsouth.com/2025/05/28/peru-china-brazil-transcontinental-railway/

15. Brazil–Peru railway - Wikipedia,

accessed August 5, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brazil%E2%80%93Peru_railway

16. Trans-Amazonian Railway - Wikipedia,

accessed August 5, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trans-Amazonian_Railway

17. Brazil & China megarailway raises

deforestation warnings in the ..., accessed August 5, 2025, https://news.mongabay.com/2025/06/brazil-china-megarailway-raises-deforestation-warnings-in-the-amazon/

18. China's Growing Influence in Latin

America | Council on Foreign Relations, accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/china-influence-latin-america-argentina-brazil-venezuela-security-energy-bri

19. What Railway Deals Taught Chinese and

Brazilians in the Amazon, accessed August 5, 2025, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2021/08/what-railway-deals-taught-chinese-and-brazilians-in-the-amazon?lang=en